Sunday, September 26, 2010

Ed abroad

One of Ed Miliband’s campaign messages was his opposition to the Iraq war. As he wasn’t an MP at the time of the invasion, he was arguably spared the difficulty of rebelling against the government. Taking a stand against Blair and the majority of the cabinet could have hindered his progression. Nevertheless he opposed it and this has been one strand of a so-called left wing approach to his leadership. His criticisms of the war have also been important in presenting himself as an honest politician who is prepared to accept past mistakes and learn from them. The loss of trust in 2003 has never been restored for many voters.

Learning from the mistakes from Iraq is a relatively easy thing, there are so many to choose from. So this stance doesn’t really give him any differentiation from most, although it did create a clear difference with his brother. But creating a new ethic for foreign relations requires more depth. Ed has advocated a values based approach, as opposed to a traditional alliance based one.

David Cameron congratulated Miliband on his victory and promised to share information on issues of national security. Being privy to this information will probably help form Miliband’s foreign policy. He has stuck to the national consensus on Afghanistan during his campaign – that a withdrawal should take place only when a degree of security is achieved. But as issues arise – he will have to react in a pragmatic way, rather than playing solely to the Labour left. The withdrawal from Afghanistan and Trident renewal will test the theory that he owes the Unions for his win.

Another clue to Miliband E foreign policy lies in Miliband D. Ed has stated that he wants to use David’s talents within his shadow cabinet. The position of Chancellor might be some sort of consolation but it would be unpopular with Ed Balls, an important cabinet figure, and David’s new labour tendencies would contradict Ed’s social democracy message. A real likelihood is that David will retain his foreign affairs brief and as shadow foreign secretary he will be aloof from the core of power. Ed might give David free reign over the foreign brief. David will be able to retain a degree of independence that will ease the pain of losing to his younger brother.

Labour’s stance towards foreign policy for the next parliament will mostly be underpinned by two resounding factors. Firstly the Blair era provided a torrid experience to party members and nearly destroyed Labour. The leadership won’t mistake the same mistakes again. Secondly the economic situation will enforce a conservative approach to foreign affairs. Domestic politics will be of the main concern to UK voters when facing cuts – they will expect Labour to show the same focus.

Tuesday, August 3, 2010

Mexico – the forgotten neighbour

The emergence of a major drug war in America’s neighbour has been largely unnoticed. The wars in the Middle East had dominated the Bush administration’s foreign policy. Besides Mexico falls within a policy gap – is it domestic and regional? And it was only recently that proper statements were made by senior administration officials. Now Hilary Clinton has drawn parallels with the Colombian narco wars during the 1980s.

The similarity between the Colombian drug wars of the 1980s and 1990s and the Mexican cartel wars is strong. Then two cartels – Medillin and Cali – waged a long war against the state, local officials and anyone else who was in the way. The situation was arguably far worse with powerful narco-paramilitaries attacking state institutions, intimidating or killing police and government officials, and often allied with insurgent groups like Farc, controlling large areas of the country. The over used term ‘failed state’ certainly applied to Colombia in the 1980s as no sector of society escaped cocaine related violence. The Colombian cartels also established distribution networks through Central America, the Caribbean and in the United States itself.

Most of these Colombian conditions apply now to Mexico. Local officials and police are largely compromised by corruption or face threats of violence. In a slight comparison to Colombia, the Mexican violence is more focused on inter-cartel battles. But the Mexican state is still under threat, the cartels have attacked government officials and are now facing a full square conflict with the army. But narco-terrorism is not as prominent as it was in Colombia. The cartels have looked to establish regional control though: replacing trade routes once managed by the Colombians and expanding to American cities and even to Europe and West Africa.

The Colombian war was undoubtedly violent: caused by a combination deep rooted political tensions, an unprecedented increase in wealth for the traffickers and social inequality that fed general criminality. The Mexican war has these characteristics. But other factors have brought on the conflict since 2006 and made it especially violent. The fact that all other supply routes for drugs (especially cocaine) have been sealed means that the US-Mexican border is a concentrated point for traffickers to supply the north. The Caribbean-Miami route was restricted by US agencies from the late 1980s. This has increased the profits for north Mexican cartels but also raised the stakes. With such lucrative rewards, the cartels have resorted to greater violence to ensure their share.

Another cause of such extreme violence has been the ease with which guns, especially automatic weapons, cross the border. The figures are disputed by organizations like the National Rifle Association, but supply of weapons is certainly a factor in inflaming the violence. This has included military grade hardware such as RPG launchers, explosives and even tanks. Desertion from the Mexican army has played a role, in particular the former special forces soldiers who formed the notorious Los Zetas, now one of the most feared and violent groups.

Some argue that the war is a war of choice, initiated by Frederick Calderon following his 2006 election. His decision to send troops into the northern towns certainly coincided with the violence, but the problems of Mexico have been in gestation for a long time. A spike in violence would have been inevitable and as most of the violence has been intra-cartel, it would suggest that the military are another player in the conflict not a lead protagonist.

The one constant in the war is the American consumer. The continuous demand for drugs, not just cocaine and marijuana but also metamphetamine and heroin, has fuelled the criminality. The critics of the war on drugs argue that successive governments have failed to grasp this elementary fact. Decriminalisation would starve the traffickers of their lifeblood. How the actual supply end would remain free of criminality is unclear. The traffickers are linked to the process at every level – how would it be possible to bring these individuals onside. A criticism of decriminalisation is that criminals would still act as criminals – operating in other black markets. In areas of Latin America where poverty is deep, the causes of drug related criminality may well exist.

Wednesday, February 24, 2010

Iraq and the press

The threat justification was the hardest to prove. Firstly as threats like risks are perceived and the threshold for any threat will vary. The threat of WMD has been with us since the end of the second World War. Arguing that such a threat has worsened is not an easy task. Whilst Saddam had used and developed WMD in the past, it was unclear whether he retained this capacity. Secondly to justify war the Western powers would need to rely on intelligence gathered covertly from a mixture of unreliable and sparse sources. The intelligence agencies across Europe and the United States were convinced Iraq still possessed chemical, biological and nuclear capability or at least the ambition to develop. Clearly unable to provide open access to their sources, politicians had to present their evidence via the media in various dossiers, intelligence reports and press briefings. In the run up to war favourable media was used to present this case; sections of the media opposed to war scrutinised it.

Clearly from hindsight the evidence did not match the reality. But the public generally saw no reason to doubt the intelligence agencies who had been the vanguard of foreign policy for centuries. In an age of scepticism there were many who doubted the concrete nature of what was presented. Simile those opposed to war on humanitarian or anti-imperial grounds did not necessarily doubt that Saddam had WMD, but fiercely opposed the solution being set out by the Bush administration.

The good faith displayed by the media to the WMD argument proved to be finite. As it became obvious that the WMD did not exist, the media changed tack and sought to prove that politicians had spun, exaggerated or lied about the exact nature of what Iraq possessed. The war between the BBC and the government in June and July 2003 that led to the Hutton inquiry was the apex of this. Sections of the media who maintained a grudging acknowledgement that Blair was right and Saddam needed to go, reverted back to traditional positions. The Daily Mail, Telegraph and Times were critical of the way intelligence had been presented to the public, despite supporting the war. A hatred of new Labour, its ways and personnel superseded support for war.

The British media's focus on the September dossier and the semantics of Blair's statements on WMD have been an obsession, that has often baffled Iraqis. Pretty much since late May 2003 when the accusation of exaggerating intelligence emerged, large sections of the media have focused on this unremittingly. The questions about WMD and Blair's veracity provide a focal point for all opponents of the war to hone in on. The obsession to prove that Blair, Campbell and anyone else connected lied often seemed more important than what was actually happening in Iraq. Simile the debate over whether Iraq was in a state of civil war in 2006 formed part of a totemic struggle between the government and the media. To the government Iraq wasn't; to the media it was – thus vindicating their previous opposition.

The absence of Iraq experts in the mainstream media is also a criticism of how the war was reported. Prior to the war, Iraq's closed and secretive society meant that prior experience of Iraqi culture was rare. After the invasion and in the dangerous aftermath, those reporters who were new to Iraq would be unable to truly get to know the country. There would be no learning curve for new reporters. Either reporting would be from a distance within the Green zone or embedded with patrols. Actually meeting ordinary Iraqis would be far too dangerous for inexperienced journalists, as the risk of kidnap and death became widespread in the aftermath. A consequence for Western audiences is that reporting trends and patterns in Iraq, that long term experience could understand, was replaced with a focus on events – the spectacular insurgent attacks or American operations that regularly occurred.

Further to this, as the insurgency developed through 2004, its nuances were poorly reported. True the actual fabric of the insurgency was not fully understood by defence intelligence let alone journalists. But the American line that the violence was caused by outsiders whether in terms of personnel, finance or weapons was too easily passed. The Bush administration tried to link the war to its international war on terror, but the majority of the attacks on Coalition troops were from nationalist Sunni insurgents who were alienated by the American installed process and their heavy handed tactics. Likewise violence was often linked to the new political elite that America brought in from exile.

Sunday, February 21, 2010

The Cameron doctrine?

Margaret Thatcher arrived during a period of severe domestic turbulence and British foreign policy had been in steady decline since the early 1970s. John Major's popularity had been boosted by the Gulf War but the recession was the overwhelming issue for voters. Tony Blair's vague promise of an ethical foreign policy appealed to the centre left core of his vote, but was a small part of a new fresh approach to politics that he tried to represent. Gordon Brown was the first prime minister to take office while Britain was at war for half a century. But having never mentioned foreign policy during the Blair years, apart from economic led initiatives for Africa, it was unlikely that he would start gushing out ideals on world peace. His book on courage was about the limit.

British leaders also tend to be highly reactive in their approaches to foreign policy. Blair is the exception here. The Falklands war, Gulf war, Bosnia and Kosovan conflicts each presented Britain with two questions. What degree of intervention does Britain take and how does this relate to Britain's role in the world? They all arrived unexpectedly. They all represented challenges to a Britain that has often tried to punch above its weight.

You would expect Cameron to follow this pattern of a reactive strategy. Tackling international crises, most likely with America but often with European powers, will be on an ad hoc basis. Whatever does arise will require international co-operation and so far Cameron's attempts to reach out to future potential allies has been lamentable. It's hard to believe that the Conservative party's troubled relationship with the EU won't make co-operation with European states difficult. The emphasis is on transatlantic co-operation on their website; European co-operation is not mentioned. The Tories re-position Britain's relationship with Europe solely in terms of how continental power has a negative effect, not what any positive future co-operation over foreign policy issues might be.

The one foreign policy issue that Cameron can't step back from or resist international co-operation is in Afghanistan. David Cameron has used his support for the war to draw to gain strong backing from the right wing press. But this is not necessarily part of an overarching foreign policy, it is based more in support for soldiers on the frontline. The Brown government has been accused of selling the army short and Cameron intends to be on the popular side of the argument here. A withdrawal half way through any Cameron first term would be the ideal result. Britain could then return to its traditional realist and isolationist stance, rather than the liberal interventionist outlook of the Blair years.

This return to isolationism would appeal to the Tory old guard of the 1990s who still make up a significant contingency in the party. Major was far more cautious than Thatcher in his foreign policy and after the Gulf war, Britain languished on the world stage. The ambivalence to the Balkan wars was the nadir of British foreign policy in the 1990s. Major wasn't helped by his poor relationship with Bill Clinton either. The old guard of Douglas Hurd and Malcolm Rifkind who ran foreign and defence ministries respectively are respected wise members of the Conservative party's foreign policy cognoscenti despite presiding over a dire Balkans policy. The Tories of the 1990s were so myopic that Europe was as far as their foreign policy went. There is every indication that any future Conservative government will have an equally limited outlook, with Europe being an obsession over anything else.

Assuming Britain's economy recovers and a steady withdrawal from Afghanistan can be achieved then Cameron could shift to a Blairite interventionist model. Conservatives have established links with neo-conservatives in the United States. The party has a strong right wing Jewish backing that would support strong action against Iran or any other threat to Israel. Having decent relations with allies will be crucial in such circumstances. Faced with a serious threat personal differences might be put to one side. Britain is regarded by America and Europe as a main player and is expected to fulfil these obligations.

It is also difficult to assess Cameron's intentions from his time in opposition, as they have acted primarily as an opposition party on many issues, rather than putting forward a consistent stance. They supported the Iraq war as much if not than Labour, but criticised the aftermath. They have been happy to watch the Labour party squirm during the Chilcot inquiry but know that they have been lucky to avoid scrutiny of their role. They criticised disproportionate Israeli action against Hezbollah in 2006, but have portrayed themselves as a dedicated supporter of Israel on most other occasions. Accusations of opportunism and inconsistency can be easily aimed.

A recent presentation at Chatham House by Cameron's foreign policy team failed to clarify their aims. Dame Pauline Neville Jones explained that a Conservative foreign policy would be more pre-emptive and intelligent in its approach, which is to expected. That is what the foreign policy establishment do all day. Foreign policy is also, as previously stated, often reactive to events. A doctrine cannot ever work if it doesn't factor in the unexpected. Cameron will probably learn this quite soon after taking office.

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

Iraq's fateful election

The two alliances that look most likely to gain the most seats, cover the majority of the potential Shia vote, the Iraqi National Alliance (INA) and the State of Law Alliance (SOLA). The INA won the 2005 election and includes the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq and the Sadrist movement. SOLA takes a more nationalistic approach and includes current prime minister Maliki. Other parties include Sunni alliances the Iraqi National Movement and Unity of Iraq Alliance. The Kurdish parties have formed an alliance to cover the Kurdish representation.

The introduction of democracy to Iraq after years of dictatorship and one party rule has been fraught. Elections have taken place – true, but the desired consequences have not always followed. The elections of 2005 confirmed the Sunni population's fear of marginalisation, after a limited participation. The elections have also appeared as something of a sideshow besides the raging violence that has overwhelmed Iraq. Successful elections have not led to political stability.

The elections of 2005 took place whilst insurgents waged war against the Americans and Iraq's embryonic state. The threats to bomb polling stations weighed on any Iraqi voter. The 2005 election resulted in a Shia-Kurdish victory, but the deterioration that followed wasn't just caused by Sunni rejection. The rejectionist forces opposed the entire new Iraq project, not just the electoral process. And vowed to wage war regardless. The December 15th 2005 elections did see some participation from Sunni insurgent groups keen to gain political power. These splits between nationalist insurgent and Islamist insurgent could be traced back to this difference of attitude.

The failure of elections to provide national unity and an end to sectarian differences also worsened inter communal violence. Unable to come to a political settlement, Iraqi politicians drew on their militia links to press home their influence. The militias integration into ministries of the state – acting as personal fiefdoms for Shia politicians – further alienated the Sunnis from the political set up. Elements within the Shi'te political fabric were more interested in controlling power than power sharing. Whilst clearly partisan Noura Al-Maliki has provided a counterweight to the power hungry Sadrist party. The previous elections created clear divisions in Iraq into sectarian lines. Tensions that did not previously exist were formed. Power and the expansion of power encouraged coercive and often violent practices by Iraqi politicians.

Despite recent improvements, the security threat in this election is still very real. The recent large attacks by Ba'athist-Al Qaida linked militants has been focused on the symbols of government power – ministries of health, justice, etc. But personal security for Iraqis is still poor, it just isn't reported extensively by the Western media. Iraq heads into these elections in a weak position.

The Americans will hope for a predictable outcome where established power bases keep their control. Iraqi domestic politics are now firmly considered Iraqi affairs. Greater participation from Sunnis, especially former insurgents like the Sons of Iraq, is to be hoped for. Kurdish confidence in the political system is also important to avoid a Iraqi-Kurd Arab split. The fault line that divides northern Iraqi Kurdistan and the Sunni heartland could be the new battle front. America will also hope that Iraqi politicians resist further Iranian influence. This is difficult to expect but will be crucial to wider US-Iranian relations that have worsen considerably of late.

Tuesday, February 2, 2010

Iran and the US - at breaking point

Surely this situation cannot continue. The short answer is no. Both sides have indicated that they will not back down. The long game of brinkmanship that Iran has been playing will eventually end. The dangerous brinkmanship that Saddam engaged in prior to the Iraq invasion was supported by his belief that America would never invade. Even days prior to the actual invasion he believed that the Americans would not go through with it. Now Barack Obama is no George W Bush and is not surrounded by a hawkish cabinet, so military action is not inevitable. But the pressure on him in a Congressional election year, with a relative decline in his popularity and with a frenzied Republican right, would be too great for him to, if not actually authorise military action, at least give tacit support to Israeli action. It is hard to stay optimistic given the characters involved and the political context of Iran-US-Israeli relations, but in this article I'll try.

The way things stand Iran, Israel and the United States are on a collision course. It is safe to say that the policy of any one of them will not dramatically change with their respective leaders. But the one constant that might change is Iran's domestic political situation. If there is going to be a solution to the nuclear crisis then it will come from here. On the one hand, the nuclear card has often (and could henceforth be) been used to shore up domestic support amongst a patriotic population. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's recent nuclear rhetoric has been ratcheted up to try and distract from deep internal opposition to his presidency. But once the consequences of such a nuclear policy become apparent, with sanctions and further economic isolation, internal opposition will only grow. Reformist leader Mir Hussein Mousavi pledged his support for Iran's nuclear programme in the June elections, but his pragmatism is clear. Besides, any candidate who pledged to scrap Iran's nuclear programme would not have been permitted on the ballot paper, with Iran's strictly controlled electoral system.

Looking from hindsight it was probably a mistake to President Obama to be so impartial during the election protest last year. A declaration of American commitment to human rights and democratic integrity is not the same as meddling in another countries affairs. Iran's leaders blamed the West anyway for the post election unrest, despite Western government's going out of their way to keep schtum. Given the fragility of the situation, knowing what kind of covert activity America is undertaking in Iran, would be difficult. The Iranians have made various claims of foreign espionage plots involving American hikers, journalists or just simply foreign infiltrators. None have come across as anything but the result of the regime's paranoia. Either the Americans are acting very carefully or dare not create an incident that could trigger a serious escalation. As with today's assassination of a nuclear physicist – the initial blame was put on America and Israel but was denied immediately.

A game of psychological warfare is being played out. You can guarantee that America has a legion of analysts and Iranologists de-cyphering messages emitting from Tehran, whilst trying to determine who holds the power in Iran's opaque political system. Iranian psychology might often seem simple and naïve but is equally thoughtful. Every incident in Iran's turbulent domestic scene can be passed off as a foreign plot onto an often gullible public. The Iranian leadership might be ignorant of global politics but they know how to play international powers off one another, stall negotiations and maintain ambiguity.

Having an influence on how Iran's domestic battle evolves, is way beyond America's reach. It is doubtful whether sanctions could hurt the factions America wants to weaken. Helping exiles might be an answer. On the downside, after the Iraq experience, exiles can often provide false information and be unrepresentative of the actual population. The ruling elite has a tight control, so what counts is what occurs in protests in Iranian cities. But even though the internet and external communications are censored, knowing that foreign exiles and supporters are strong and organized outside Iran, would embolden the domestic protesters.

Sunday, December 6, 2009

Afghanistan 2012

Whereas Iraq was a war of choice, initiated by America and with modest international support. Afghanistan was widely accepted as needing intervention after September 11th and NATO's invoking of Article 5 sealed a wider international effort. If the September 11th plots had emanated from say Somalia, punitive strikes and withdrawal might have sufficed, but Afghanistan's strategic location – its proximity to Pakistan, Iran and China – means that it cannot escape attention. If we base our future hopes for country within this geographical context – failure seems unthinkable. But given the vital importance that Afghanistan has to its neighbours, success should be certainly possible. China, Iran and Russia all have an interest in a stable Afghan state. Clearly the actual material contribution – troops especially – could be limited. China has been approached for humanitarian and training assistance. A significant international role is certainly many Chinese see as long overdue. Afghanistan's natural wealth is appealing and investment by Chinese companies – in a similar way to Africa – could be feature of the country's future redevelopment. China needs to contribute in other ways though, if it is to reap the rewards.

Russia's history with Afghanistan makes any involvement difficult. President Obama has sought Russian assistance in more tangential ways – the use of Russian airspace for American supply lines was discussed in April, but has failed to become a reality. The opening up of Russian airspace would solve many logistical problems, especially if American troop numbers increase. But the historical enmity between the Cold war foes and administration complications like transit fees are hindering the deal. An Afghan future would be internationalised – having two world powers close to its borders means it can be easily exploited for the better.

Most Western diplomats will hope that an Afghan future is free of corruption for which President Karzai's election result has come to epitomise. Replacing Karzai or somehow marginalizing him might be the best way forward given the cancellation of the run off with Abdullah Abdullah. The creation of a loya jirga of tribal chiefs would be more balanced than the dominant elite that Karzai represents. The expansion of the national decision making process to the many under represented Afghan ethnic groups would help solve some of the intense division that exists in the country.

Wishing for a democratic redeveloped Afghanistan is great, but this is almost solely based on progress against the raging insurgency. Taliban attacks occur daily across the country with no real safe havens. Discussions of withdrawal fill Afghani politicians with dread. The stark warning that the Taliban would overrun Kabul in days if NATO withdrew has emphasised how serious the conflict has become. These pessimistic statements disguise the mixed reality on the ground, where reconstruction and development are being undertaken by NATO troops. The McCrystal counterinsurgency plan has started – protecting the local population and building confidence between Afghans and foreign troops. An Afghanistan of the future would somehow have overcome these barriers between the foreign and domestic. Cultural differences are vast, but shared goals of peace and economic development exist. Democracy and political freedoms might have to wait.

2012 is a few years away but it is only three years. Not much time for things to happen. The NATO coalition are realising that patience is one of the traits that will win this war. Training troops, curbing corruption and reconstruction will take a long time. The ingrained ineffectiveness of domestic police and army; the unreliability of Karzai's administration; 30 years of war, all require a long term commitment to overturn. The Obama administration has to balance between showing commitment to Afghanistan and Pakistan, but not giving an indefinite length to their involvement, a consideration needed to ensure domestic support. No progress in eight years has made the American public weary, but it may well take at least another eight or more.

Afghanistan's future has been linked to Pakistan for far longer than the current conflict, so it is a truism that both futures are interlinked. But 2012 Afghanistan will be equally defined by what is occurring in other neighbouring countries. The situation in Iran could turn worse than it currently is and totally dwarf the Afghan conflict. A regional war following an Israeli or American attack on Iranian nuclear facilities would most likely shift the focus westwards. Iran's allies lie to its west, so Lebanon, Syria and Palestine would focus American attention away from Afghanistan. This is not to dismiss some sort of Iranian attack on American forces in Afghanistan. 2012 will be an American election year and Obama will be focused on protecting Israel and Saudi Arabia, over anything else.

Sunday, November 22, 2009

Iraq – opinion still divided

The Iraq war was a unique conflict for British domestic politics in that it divided both the left and right. The British left was split between a policy of humanitarian intervention and an anti imperialist opposition to the conflict. The right saw Saddam as a threat but the realist right preferred to keep the status quo. The media also adopted conflicting positions. Papers like the Mail put their pathological opposition to Labour over opposition to British involvement. Despite having clear concerns over terrorism. The Sunday Telegraph was pro war in the run up with questionable reporting from Con Coughlin, but has always been happy to attack Labour since. Leaked documents on the eve of the Chilcot inquiry are designed to set the narrative for the forthcoming inquest. The Iraq war is still a very large stick to attack political opponents with.

The legacy of the Iraq war still also has reverberations for the individuals involved. The EU's quest for a President had Tony Blair in the running, advocated by Gordon Brown. But the opposition from European politicians and the British media over his involvement in the war presented a brick wall of dissatisfaction. Other British political figures, like Hoon, Campbell and Straw have varying degrees of influence these days, but it would be hard to argue that the war and its aftermath didn't deal a severe blow to the longevity of their political careers. The great survivor is probably Brown, who acquiesced with the decisions, but made next to no statements at the time. The American players have mostly moved on either to retirement, think tanks or the private sector. America's executive system that enables political appointees rather than democratically elected representatives to take foreign policy decisions has meant those involved are no longer in any position of power. The shift towards Democrat power that began with the midterm elections of November 2006 has for better or worse closed a chapter in American politics. The war was less controversial in America, at least amongst the political class, so the quest for answers and even retribution that exists in Britain, does not follow across the Atlantic.

The academic debate keeps the invasion of the Iraq war relevant. Some academics argue that Bush foreign policy is no different from the American tradition and that future scenarios like pre 2003 Iraq will be treated simile. The decisions made in late 2002 are still under archive and until the day they are opened to scrutiny, academics say we should reserve judgement. Academic input has been brought into the Chilcot inquiry at an early stage. But this feels so late, the absence of academic consultation on Iraqi culture, society and history was a fatal error in planning for post invasion Iraq. There have been numerous explosive accounts by journalists and military men who were on the ground after the invasion. This has forged the public's view of how the conflict unfolded. But the academic's job is to collate this first hand primary research and present it within a cogent framework, explaining what exactly happened. Academics like Toby Dodge, Charles Tripp and Richard Haass and Kenneth Pollack have presented ongoing academic analysis but now as the Iraq conflict moves on and America contemplates withdrawal, a broader narrative might develop.

When the debate rages over the decision to go to war, a sort of collective amnesia descends. What was the context behind the events leading up to 2003. From the American perspective a decade of failed Iraq policy culminated with the invasion. For Britain, the problem was depicted in the media as a recent issue, but it had burned in foreign affairs committee rooms in Washington for twelve years.

The critical view of American foreign policy catalogues a series of policy blunders. Firstly the failure to understand Iraqi politics in 1991 and expectation of a coup. Second a failed and ambiguous containment policy that left America impotent and allowed Saddam to disregard all UN resolutions. Then finally, a total misconception of how America would be received in 2003 and no plan to reconstruct the country. The context was one of failure on both sides and this should be remembered when assessing the decisions of late 2002.

The errors in American strategy were mirrored by Saddam's reckless behaviour and the nature of regional Middle Eastern politics where saving face ruled decision making. Saddam invaded Kuwait to secure his position amongst the military elite, whilst also being totally ignorant of western politics and the potential outcome of such an act. His brinkmanship with the United States and pretence of possessing WMD to deter Iran brought war on his country, but both in 1991 and 2003 Saddam did not believe that America would invade.

9/11 changed everything etc. True to an extent. It lowered the threshold, it reiterated the fear of a terrorist-WMD nexus, it installed a climate of fear in the American public. But the reasons for invading Iraq were the same before 9/11 as they were after. The Iraq Liberation Act of 1998 had set in law the desire for regime change. Saddam's supposed breaches of UN resolutions and international law were regularly used as the legal basis for regime change in 2003. The WMD argument was an extension of the argument, not the meat of it. A re-evaluation of the American argument for war will most likely emphasise this point. That 9/11 didn't create a massively different mindset, the plan to remove Saddam was a key Bush administration goal from the time it came to office.

Saturday, November 7, 2009

The fourth 9/11 - another revolution?

If we had to plot ahead and look for this next seismic moment, where and what would it be? The collapse of American forces in Afghanistan, airstrikes on Iran by Israel, or an implosion in Pakistan? The twentieth anniversary will provide commentators and contemporary historians ample space to consider how the world has progressed since, but history tells us that another defining moment could be just around the corner. We will then - twenty years after - be faced with a whole new set of consequences to deal with.

Critics of Western foreign policy highlight the wasted opportunity that followed 1989: the "peace dividend" dissipated as regional conflicts continued and authoritarian regimes retained their grip. Fukuyama's End of History predicting the dominance of Western liberal democracy was blocked by autocratic rule in the Middle East and Russia's return to traditional authoritarianism, after initial steps towards democracy. Whilst American policy makers espoused this new era in the early 1990s as ripe for the expansion of democracy, the reality never quite matched the rhetoric. True Latin America democratized as did South East Asia, but Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Jordan - key allies in the Middle East - stagnated in expanding popular representation. The rise of militant Islam was driven by a perceived apostasy (and lack of popular accountability) in these repressive allies. The 9/11 attacks were part of Bin Laden's strategy to polarize the Arab street and spark revolution against this authoritarian rule. A 1989 style of revolution in the Middle East would have been Osama's dream outcome. But given the way democracy has been curtailed in the region in the last decade, it may not be for a while

Tuesday, July 28, 2009

Iran - the moment of truth

Israel has long predicted that Iran will have enough enriched uranium to build a nuclear weapon by sometime in late 2010. Assuming Iran is prepared to negotiate then, Obama and Khameini will have a year or so to thrash out a deal. But with Khameini's position severely weakened by the recent post-election protests and Ahmadinejad in an even weaker position than he was prior to his "victory", any substantive diplomatic moves seem incalculably complicated. The nuclear clock will still be ticking regardless of the internal power struggle in Iran. It is not inconceivable that a full blown political crisis is taking place in Iran, whilst the country crosses the nuclear threshold. How the rest of world - specifically the United States and Israel - respond under those circumstances is impossible to say.

Following Iran's dramatic June, a quieter July - on the streets at least - has followed. But behind the scenes political struggle has rumbled on. Now Ahmadinejad and Khameini have fallen out over the president elect's choice of vice president, Esfandiar Rahim Mashaie, who had previously describing Iran as a friend of Israelis. Ahmadinejad defied the supreme leaders demand for Mashaie to be sacked. The following day, Ahmadinejad fired the country's Intelligence Minister, Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejeie, who was subservient to Khameini. This spat - almost unthinkable a month ago - shows the ruptures that have opened since the election. The United States cannot have failed to notice and internal disagreements like this, will weaken the Iranian leadership in any nuclear negotiation.

What happens next to Ahmadinejad is obviously critical. For Khameini to drop him and call another election would be an astonishing turn around. If he was forced out, it would most likely be done in a drawn out manner to avoid such a loss of face for the Supreme leader. The consequences and possible backlash from Ahmadinejad's allies in the Republican Guard could be even more dramatic. Grasping the outcomes for Iranian politics at the moment is extremely challenging, as knowing what exactly is happening in the corridors of power is very difficult and as this is unchartered territory. Such internal dispute has never occurred within Tehran since 1979.

Ahmadinejad could be out then and a compromise between the Khameini camp and the Mousavi-Rafsanjani-Khatami alliance seems a possibility to ease Iran through this period. Who would emerge as president is very unclear. Mousavi regards himself as a defender of Ayatollah Khomeini's Islamic revolution, having served as prime minister in the 1980s. His belief is that Khameini has betrayed the ideals set out from 1979. Given this and ff Mousavi emerges in the power, how he deals with the nuclear negotiations is a whole new question.

Fisk on Arab culture

Why is the Arab world – let us speak with terrible sharpness – so backward?

Why so many dictators, so few human rights, so much state security and torture,

so terrible a literacy rate?

Why does this wretched place, so rich in oil, have to produce, even in the age of the computer, a population so poorly

educated, so undernourished, so corrupt? Yes, I know the history of Western

colonialism, the dark conspiracies of the West, the Arab argument that you

cannot upset the sheikhs and the kings and the autocrats, the imams and the

emirs when the "enemy is at the gates". There is some truth to that. But not

enough truth.

Once more the United Nations Development Programme has popped up with yet one more, its

fifth, report that catalogues – via Arab analysts and academics, mark you – the

retarded state of much of the Middle East. It talks of "the fragility of the

region's political, social, economic and environmental structures... its

vulnerability to outside intervention". But does this account for

desertification, for illiteracy – especially among women – and the Arab state

which, as the report admits, is often turned "into a threat to human security,

instead of its chief support"?As Arab journalist Rami Khouri stated bleakly last week: "How we tackle the underlying causes of our mediocrity and bring about real change anchored in solid citizenship, productive economies and stable

statehood, remains the riddle that has defied three generations of Arabs." Real

GDP per capita in the region – one of the statistics which truly shocked Khouri

– grew by only 6.4 per cent between 1980 and 2004. That's just 0.5 per cent

annually, a rate which 198 of 217 countries analysed by the CIA World Factbook

bettered in 2008. Yet the Arab population – which stood at 150 million in 1980 –

will reach 400 million in 2015.I notice much of this myself. When I first came to the Middle East in 1976, it was crowded enough. Cairo's steaming, fetid

streets were already jam-packed, night and day, with up to a million homeless

living in the great Ottoman cemeteries. Arab homes are spotlessly clean but

their streets are often repulsive, dirt and ordure spilling on to the pavements.

Even in beautiful Lebanon, where a kind of democracy does exist and whose people

are among the most educated and cultured in the Middle East, you find a similar

phenomenon. In the rough hill villages of the south, the same cleanliness exists

in every home. But why are the streets and the hills so dirty?

I suspect that a real problem exists in the mind of Arabs; they do not feel that they own

their countries. Constantly coaxed into effusions of enthusiasm for Arab or

national "unity", I think they do not feel that sense of belonging which

Westerners feel. Unable, for the most part, to elect real representatives – even

in Lebanon, outside the tribal or sectarian context – they feel "ruled over".

The street, the country as a physical entity, belongs to someone else. And of

course, the moment a movement comes along and – even worse – becomes popular,

emergency laws are introduced to make these movements illegal or "terrorist".

Thus it is always someone else's responsibility to look after the gardens and

the hills and the streets.And those who work within the state system – who work directly for the state and its corrupt autarchies – also feel that their existence depends on the same corruption upon which the state itself thrives.

The people become part of the corruption. I shall always remember an Arab

landlord, many years ago, bemoaning an anti-corruption drive by his government.

"In the old days, I paid bribes and we got the phone mended and the water pipes

mended and the electricity restored," he complained. "But what can I do now, Mr,

Robert? I can't bribe anyone – so nothing gets done!"Even the first UNDP report, back in 2002, was deeply depressing. It identified three cardinal

obstacles to human development in the Arab world: the widening "deficit" in

freedom, women's rights and knowledge. George W Bush – he of enduring freedom,

democracy, etc etc amid the slaughter of Iraq – drew attention to this.

Understandably miffed at being lectured to by the man who gave "terror" a new

name, even Hosni Mubarak of Egypt (he of the constantly more than 90 per cent

electoral success rate), told Tony Blair in 2004 that modernisation had to stem

from "the traditions and culture of the region".Will a solution to the Arab-Israeli war resolve all this? Some of it, perhaps. Without the constant

challenge of crisis, it would be much more difficult to constantly renew

emergency laws, to avoid constitutionality, to distract populations who might

otherwise demand overwhelming political change. Yet I sometimes fear that the

problems have sunk too deep, that like a persistently leaking sewer, the ground

beneath Arab feet has become too saturated to build on.

I was delighted some months ago, while speaking at Cairo University – yes, the same academy which

Barack Obama used to play softball with the Muslim world – to find how bright

its students were, how many female students crowded the classes and how,

compared to previous visits, well-educated they were. Yet far too many wanted to

move to the West. The Koran may be an invaluable document – but so is a Green

Card. And who can blame them when Cairo is awash with PhD engineering graduates

who have to drive taxis?And on balance, yes, a serious peace between Palestinians and Israelis would help redress the appalling imbalances that

plague Arab society. If you can no longer bellyache about the outrageous

injustice that this war represents, then perhaps there are other injustices to

be addressed. One of them is domestic violence, which – despite the evident love

of family which all Arabs demonstrate – is far more prevalent in the Arab world

than Westerners might realise (or Arabs want to admit).

But I also think that, militarily, we have got to abandon the Middle East. By all means, send the

Arabs our teachers, our economists, our agronomists. But bring our soldiers

home. They do not defend us. They spread the same chaos that breeds the

injustice upon which the al-Qa'idas of this world feed. No, the Arabs – or,

outside the Arab world, the Iranians or the Afghans – will not produce the

eco-loving, gender-equal, happy-clappy democracies that we would like to see.

But freed from "our" tutelage, they might develop their societies to the

advantage of the people who live in them. Maybe the Arabs would even come to

believe that they owned their own countries.

http://www.independent.co.uk/opinion/commentators/fisk/robert-fisk-why-does-life-in-the-middle-east-remain-rooted-in-the-middle-ages-1763252.html

Monday, July 27, 2009

Lebanon's perfect fragility

West Beirut's Hamra district is now an moderately affluent, often quiet, neighbourhood. Hamra Street is a busy day time shopping zone; the streets leading off have many cafes, boutiques and local stores. Hamra is a perfect mix of residential and busy Beiruti everyday life. But in Lebanon's civil war, West Beirut and Hamra in particular was the centre of fierce fighting. A Sunni district, Hamra was home to numerous militias including the socialist al-Murabitoun, Syrian backed groups and, most significantly, the PLO. Only last year, Hamra was deserted again as Hezbollah and Future Movement militia clashed over several violent days.

To the north of Hamra, lies the Corniche – a long seafront promenade. With perfect viewing for watching the Mediterranean sunset, this walk is a relaxing spot for all Beirutis to unwind. Overlooking the Corniche is the famous American University of Beirut (AUB). The lessons are taught in English, so the cafes of Bliss Street besides the campus, are filled with Lebanese chatting in American accents (not Americans). The campus is a peaceful distance from the Beirut noise, but during the Civil war it was not able to keep out of the violence. Guerillas used the grounds to display their rockets to the international press in 1976 and the former president Malcolm Kerr was assassinated in 1984. The University insisted that it remain open during the war.

From the roof terrace of the Mayflower hotel, you can see uncountable buildings. It is impossible to distinguish between the old and new blocks. The buildings have seen it all. Many have witnessed the terrible days when Hamra was a battlefield. But the new ones are testimony to the Lebanese's desire to rebuild and construct a positive future. The fact that you can't differentiate between the two sums up this internal conflict between forgetting the past and taking steps towards a better future. The Mayflower Hotel is a wonderfully anachronistic place, filled with pictures of 19th century Britain, with previous guests including Graham Green, Kim Philby and countless journos during the war.

North of the National Museum – which displays artifacts of the Phoenecian, Roman and Hellenistic periods – lies Beirut's infamous Green Line. Now simply a busy street, it marked the frontline in the civil war, dividing the predominantly Muslim West and Christian East. The only real leftover from this partition is a thick plain wall with large bullet holes. Continuing north you arrive at Place de Martyrs where numerous political rallies have taken place, which is besides the Mohammed al-Amin mosque, built by Rafiq Hariri before he was killed.

Beirut's Downtown district was decimated during the war and has now been redeveloped into an impeccable area of the city. There are several streets leading off the Place d'Etoile with restaurants and shops. It feels more like Europe and there is definitely no riff-raff. It may lack authenticity but it is probably the most modern part of the city. All entrances to the area are manned by checkpoints so it is also the city's safest spot.

A short distance north near the seafront is the St George Yacht Club. Two buildings stand without their fronts, having been blown off by the truck bomb that killed former prime minister Rafiq Hariri. When you visit this location, you can understand the motives of his killers. Firstly it is in a central location in Beirut, almost between East and West. Secondly it is overlooked by large hotels and apartment blocks built by Gulf money under Hariri's guidance. The assassination strikes at the heart of this wealth and power.

Central Lebanon remained largely undamaged in the July 2006 war. The Shia southern suburbs, home to Hezbollah, were subjected to heavy Israeli bombing. The Shia may often be the poorest section of Lebanese society, but they arguably hold the power. This power lies in two critical areas: demographics and weapons. The absence of any census in Lebanon or serious survey of the respective sectarian populations means that an estimation of total Shia is very difficult. The traditional figure of 35% is passed around, but our Shia taxi driver had four brothers and five sisters alone. The Shias also have Hezbollah of course. Being able to resist Israel's onslaught in 2006 proved that it is no mere mediocre militia and it managed to take control of central Beirut last year with relative ease.

Wednesday, June 17, 2009

Iran - the latest

The Huffington Post is also providing a running blog. They have some excellent footage of today's protests: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/06/13/iran-demonstrations-viole_n_215189.html

Despite the ban on reporting by foreign journalists, the unstoppable Robert Fisk is defying the regime and reporting on the situation: http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2009/06/17/2600571.htm

Monday, June 15, 2009

The Green Tide

The reaction of the current government to this "victory" has been to block websites, telecommunications and email. But with such a media savvy youth leading the protests, the possibility of comprehensive censorship seems unlikely. There won't be a repeat of Burma, where the junta shut the country off. But with a population of 40 million, people power is proving overwhelming. Iranians are extremely politically aware with the advent of the internet. The Islamic regime's efforts to offer freedoms to the people but then deny them their desired result, has proved a disastrous strategy. The genie is out of the bottle.

The depth of protests and opposition to the election's outcome means that there either might be a recount or the election is run again. But Ahmadinejad and the hardliners will fight this. After all the election was predicted to be close and the current president has strong rural support. The ominous warning before the election, that a green revolution would not be tolerated, shows the regime's culpability. Fearing this, they promptly rushed out results giving Ahmadinejad victory.

The ongoing nuclear negotiations and the other regional issues mean the outcome of these protests couldn't come at a more critical point. America has to keep quiet on these events, Iran has long seen the United States as the meddler in their domestic affairs. Which ever way the election goes, America will still have negotiate with Khamenei, unless there is a full blown revolution.

http://www.facebook.com/home.php?ref=logo#/pages/Mir-Hossein-Mousavi-/45061919453?ref=nf

It has been reported that Khameini reneged on a deal to allow Mousavi the presidency, with the hardliners re-seizing the initiative. But it seems that these aloof clerics were totally ignorant of Iranian popular sentiment and their desires for freedom and democratic ideals. Most regimes or ideologies have a limited lifespan. Are we seeing after just over 30 years the end of this one? The revolutionary theocracy has become isolated from the real world and has now alienated its own longstanding supporters. This can't be blamed on foreign interference. This is now domestic pure and simple.

Monday, June 8, 2009

Lebanese elections

http://www.cfr.org/publication/19580/gauging_hezbollah_after_the_vote.html?breadcrumb=%2Fpublication%2Fpublication_list%3Ftype%3Ddaily_analysis

Thursday, June 4, 2009

A Historic Speech?

Wednesday, June 3, 2009

Iranian Culture Wars

An ongoing exhibition at the British Museum depicts the life of Shah Abbas, the ruler of Persia from 1587 to 1629. He established contacts with Europe during his reign, to gain an advantage against the greater enemy – the Ottoman Empire. The ruler would even be mentioned in Shakespeare's Twelfth Night, under the name “the Sophy”. This was the last time in Iran-West relations where a mutual respect and parity was felt by both sides. As European colonial expansion settled in Asia, Iran's purpose was limited to its location as a valuable trade route. This economic relationship would become progressively less favorable to Iran as the decades passed.

Thirty years on from the Iranian revolution, a generation of Iranians exists with little memory of the 20th century Shah - Mohammed Pahlavi, the upheaval during the period of Khomeini’s return or the violence that followed - domestic repression and war with Iraq. The current leadership was born in the fires of those early days of the revolution - where repression mixed with anti-Americanism and Islamism. That revolution was born in economics and social unfairness, then morphed into a religious and totalitarian struggle, but it now might be shifting back to the same old grievances. Ahmadinejad’s one positive selling point is his perceived distance from the stain of political corruption, but he is part of a system that limits power to the few. Iran may be a democracy but the power lies close to Ayatollah Khameini and his inner circle.

The forthcoming elections place the incumbent against two reformers candidates, Mehdi Karroubi and Mir-Hossein Mousavi. In this election, victory will lie not in what is said, but who controls how it is said.

Maybe another revolution is required in Iran - the Green or maybe Carpet Revolution. I think I need to work on these. But given Iran’s repressive internal security, a softer and more subtle revolution would be the only change possible. Internal change by stealth has greater chance of success - there is evidence that this is taking place.

Secular liberals united behind Khomeini in late 1978. The Shah’s authoritarian rule was opposed for its failure to respect the 1906 Iranian constitution. The middle class secular group the Liberation Movement of Iran, led by Mehdi Bazargan, represented the non-religious and moderate force in the revolution. Bazargan was appointed prime minister in February 1979, resigning after the students’ seizure of the American embassy. He represented the moderates: willing to compromise with the Shah’s supporters; opposing Khomeini’s cultural revolution after he resigned.

The brutal consolidation of power by Khomeini’s supporters eliminated these liberal moderate voices and all others for that matter, especially those communist. With the Iranian die cast - the students seizure of the American embassy in Tehran being the starting point - a period of extreme animosity with the West followed. Efforts towards improving relations were thin, but the first attempts were cultural. Now a restoration of these cultural relations have ever chance to empower the present day secular liberals.

In 1998 Iran invited an American wrestling team to Tehran for a tournament. In the same year the two countries played in the World Cup - Iran winning two-one. The Iranian president Mohamed Khatami had proposed a “dialogue of civilizations” in a CNN interview in 1998. Comparing Iran’s revolution to the American one 200 years previous, he suggested some profound similarities: “With our revolution, we are experiencing a new phase of reconstruction of civilization. We feel that what we seek is what the founders of the American civilization were also pursuing four centuries ago. This is why we sense an intellectual affinity with the essence of the American civilization.” Khatami’s reformist tendencies hit plenty of obstacles within Iran’s political system.

Another football march was played in 2000 in the United States. The first visit for many of the Iranians was made as hospitable as possible, with special treatment like exclusion from border fingerprinting regulation.

America's efforts to improve diplomatic relations have not run totally smoothly. The American women's badminton team was refused visas prior to a tournament in February – on a technicality not through an Iranian government block. Iran's team has been invited to the US in July. It might be a mere game of badminton, but given the antipathy that have poisoned US-Iran relations, this does matter.

Since January 2007, more than 75 Iranian athletes have taken part in wrestling, weightlifting, water polo and table tennis competitions in the United States, while 32 American athletes, including 20 wrestlers, have visited Iran, according to the Ettemaad newspaper. A total of 250 Iranian artists, athletes and doctors have made the return visit to the United States, according to the State Department.

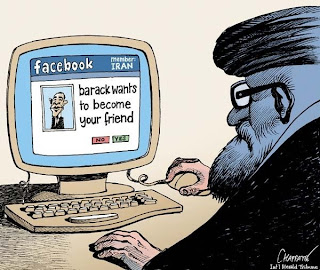

Iran’s political isolation has not always been matched with cultural isolation. Iranians - especially the younger generations - are well tuned to global opinion via the internet. Prior to this year’s elections, the authorities banned access to Facebook, only for this to be lifted. Social networking sites are seen as important in mobilizing the youth vote in these elections, with reformist Mousavi most to gain. The on/off status of Facebook is seen as a dual policy by the Iranian authorities to appeal to the country's youth, but retain control.

The final wave of soft power came this week in advance of America's 4th July celebrations. American embassies around the world are to invite Iranian representatives for fireworks, hot dogs and hamburgers, to mark America's independence.

So this month's election is finely balanced, reformist Moussavi is leading in the polls, but expect the unexpected. Ahmadinejad will say anything and do anything to stay in power; hardline candidate Mohsen Rezaei has claimed he could stop Israel in “one strike”. Whatever the result, an undercurrent of cultural connections has in many ways made a rapprochement between Iran and the West inevitable.

Sunday, May 17, 2009

Lebanon's decisive election

Since the start of the civil war, Lebanon has been a fulcrum in the region - where the forces of fundamental struggle against the secular and the international players battle regional. The consequences of a shift in the balance from one side to the other, in the forthcoming election, is being depicted by regional media and diplomats. Israel anticipates the worst - Syria is typically quiet. Clinton's visit concluded with a reserved judgement, waiting for the composition of the new Lebanese parliament before deciding how to continue their relationship. Significant advances by Syrian backed parties would not cause the same friction, that might have happened during the Bush administration. Diplomatic contacts with Syria and improved Saudi-Syrian relations have reduced the threat of post election confrontation. With the prediction that the election might end in a tie, the United States are taking a pragmatic line.

The role of Syria in Lebanon is still highly contentious. Strong relations with Syria are regarded as vital to Lebanon's national interest, not least by President Fouad Siniora, who has had a strained relationship with Hezbollah since his election as prime minister in 2005. A promotion that came about through anti-Syrian protests. In March, Syria and Lebanon established diplomatic relations, when Damascus appointed its first ambassador to Beirut. But Syria is widely distrusted still and has also been accused of interfering in the forthcoming elections.

The prospect of Hezbollah achieving power in Lebanon is a fearful one for Israel. The militant wing has reportedly replenished and vastly expanded its missile capacity since the 2006 war. Meanwhile it has publicly reiterated its support for Palestinian Islamist group Hamas. Israel has long sought a peace with its northern neighbour, it might have a government that directly opposes any peace, after the elections. Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah has made confident claims about the group's competence for governing: "I tell those who are betting on the [Hezbollah-led] opposition's failure during elections: The resistance that defeated Israel can govern a country that is 100 times larger than Lebanon". But Nasrallah is also speaking the politics of national unity: "We, Hezbollah, have always rejected the division of Lebanon and we shall always maintain this."

A series of arrests of Lebanese on charges of spying for Israel has shown the closeness of the current government and Hezbollah. The counterintelligence capacities of the Lebanese state and indirectly Hezbollah have ironically been boosted by American financial support since 2006. Hezbollah is upping its anti-Israel rhetoric before the election, part brinkmanship - part rallying cry to their voters. Hezbollah's relations with the west are still rife with suspicions, but contacts between the Islamist group and the British foreign office suggest progress is being made.

Bets are on a powersharing fudge between the two sides, held together by President Michel Sleiman. Trusted by most but still anti-Israel. The former commander of the Lebanese Armed Forces stated that "Israel was the enemy" when assuming office last year. This might not be what the international community wants to hear, but he has maintained national unity so far.

The powerbroker in Lebanon could turn out to be Christian Lebanese opposition Gen. Michel Aoun, but he has played a totally contrasting role to Sleiman. Having entered into an alliance with former enemies in 2005, his intention was to hold the balance of power. Now he resists Syrian influence, defends Nasrallah, but still holds the majority Christian support over the parties of Amin Gemayel and Samir Geagea. Aoun and Geagea have a rivalry dating back to the 1980s and the internecine "war of brothers" in 1990. But the Christian population is undecided. Aoun's position shows the contradictions in Lebanese politics - his election posters have been accused of sexism by women's groups. Who would have the greater say in a government of the March 8 Alliance is highly uncertain.

Sunday, March 22, 2009

Backtracking on renewables

Wednesday, March 4, 2009

Dealing with the inevitable

A parallel economy has existed for a long time now, involving new technologies that will reduce emissions. But a second parallel economy might be needed as well, one that deals with the consequences of climate change rather than the causes. There is a growing belief that we will have to accept climate change as a fact and limit the damage that it might cause. These inevitable changes will mean radical differences in how the world functions, where populations live and what resources we survive on. The New Scientist spells out in stark terms in its latest issue: in “a world warmed by 4 °C … it may be impossible to return to anything resembling today's varied and abundant Earth…once there is a 4 °C rise, the juggernaut of warming will be unstoppable, and humanity's fate more uncertain than ever.”

The long standing Green opposition to nuclear energy has been one of the first environmental sacred cows to be attacked in recent debate. James Lovelock - proponent of the Gaia hypothesis - was one of the first environmentalists to defy the consensus and argue that nuclear was the only realistic alternative to fossil fuels. That was five years ago and in the meantime the debate has raged, with the government pressing ahead with their nuclear energy policy. But this week four leading environmentalists have broken ranks and reiterated the nuclear case. The issue threatens to split the green movement at a critical moment.

Lovelock has more to say. His conviction is that the earth’s population will peak to 9 billion then plummet to only 1 billion by the end of the century. He also predicts that a permanent changed climate will last 100,000 years. This extremely pessimistic scenario might be extreme, but even if a fraction of his prediction comes true, then the world will be in trouble. His prediction is that a future enviro-catastrophe will resemble the apocalyptic sounding event - Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) - of 55 million years ago. He has, kindly, provided some solutions, if you can call them that. Britain, especially, will be a lifeboat of the world, so will be flooded with refugees.

How we adapt our society both in terms of infrastructure and resources is a question that academics, architects and engineers are already looking at. Events like this week’s Ecobuild conference showcase sustainable construction. With such high profile attendees, ideas for restructuring our architectural infrastructure will gain greater momentum. Obviously putting them into practice in a recession is another matter altogether. Likewise rich lists featuring the next generation of eco-entrepreneurs are admirable, but how close these individuals are to central government planning and decision-making is uncertain.

Creating new structures through intelligent engineering was well advocated in an Institution of Mechanical Engineers report - Adapting to the Inevitable. In the energy sector, the report proposes a fundamental move towards the greater decentralisation of energy production, via intelligent local networks, linked with a more internationally interconnected electricity grid to balance supply and demand differences (ie a European ‘supranational’ grid). Sources of water may need to include a higher proportion of underground storage and catchment. Greater levels of desalination may also be required and increased water recycling will become more important. The report believes that buildings adaptation is perhaps the area where most consideration of future climate change has already been made. More specifically effective master planning of urban areas to increase natural and artificial ventilation corridors. Better planned infrastructure is also required to counter possible flooding.

More radical solutions such as geoengineering are also on the cards. With origins in the Cold war and super power research into climate as a weapon, but largely outlawed by the 1970s, geoengineering now acts as a dramatic solution to an out of control problem. Geoengineering could possibly increase the reflectivity of the planet (the albedo) by propelling reflective particles into the upper atmosphere. The idea of aircraft pumping sulfate aerosols into the atmosphere might seem far-fetched to many, but it would reasonably cheap and would be applied by most nations, in contrast to the expensive and heavy investment options for cutting emissions. Scientific groups including NASA and the Royal Society have been evaluating its potential, whilst environmental groups have been cautious in their endorsement, believing that geoengineering could provide disincentives for cutting emissions. The overall effectiveness, predictability and side effects of geoengineering are questioned by the scientific community. Other risks put forward include weaponisation, geoengineering piracy or the rise of an all powerful megalomaniac with the ability to control the weather for his/her own purposes. Geoengineering could one day by the silver bullet to green issues, but until the science is conclusive, no government is going to invest substantially to take it the next step. Many of these issues are set out in an excellent Foreign Affairs essay this month: http://www.foreignaffairs.org/20090301faessay88206-p10/david-g-victor-m-granger-morgan-jay-apt-john-steinbruner-katharine-ricke/the-geoengineering-option.html